Anura Kumara Dissanayake, the leader of the self-proclaimed Marxist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), has been declared the next president of Sri Lanka.

The left-wing candidate swept polls across the south of the island this weekend, after a close contest which came down to preferential voting for the first time in Sri Lanka's history. The Tamil homeland saw another traditionally low voter turnout, with Dissanayake having a poor showing across the North-East. Districts in the Tamil homeland instead had preferential votes for his rival Sajith Premadasa.

We take a look at the history and politics of the newly-elected Sri Lankan president.

Anura Kumara Dissanayake, the leader of the self-proclaimed Marxist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), has been declared the next president of Sri Lanka.

The left-wing candidate swept polls across the south of the island this weekend, after a close contest which came down to preferential voting for the first time in Sri Lanka's history. The Tamil homeland saw another traditionally low voter turnout, with Dissanayake having a poor showing across the North-East. Districts in the Tamil homeland instead had preferential votes for his rival Sajith Premadasa.

During his campaign, Dissanayake had repeatedly vowed to dissolve parliament “the very night” of any victory. His National People's Power (NPP) coalition only has three lawmakers in parliament, and with a five-year presidential term set to commence, Dissanayake will be looking to build more support in the legislative body. He is expected to be sworn in shortly, with a parliamentary election now on the cards.

"Our journey here has been paved by the sacrifices of so many who gave their sweat, tears, and even their lives for this cause," said Dissanayake in a tweet. "Their sacrifices are not forgotten. We hold the scepter of their hopes and struggles, knowing the responsibility it carries."

The JVP leader takes over Sri Lanka’s executive presidency at a time of economic uncertainty, and as Eelam Tamils in the North-East continues to demand autonomy and justice for the genocide at the hands of the Sri Lanka state.

We take a look at the history and politics of the newly-elected Sri Lankan president.

Read more: Who is Anura Kumara Dissanayake?

Staunch Sinhala-Buddhist nationalist

.jpg)

The JVP has a storied history in Sri Lanka having staged two insurrections against the state in the early-1970s and the late-1980s. The latter of these was chiefly in response to the Indo-Lanka accord and the threat of devolved powers to Tamils.

Though the JVP proclaims itself as Marxist, for decades the party has been staunchly Sinhala nationalist – a politics that Dissanayake has proudly defended.

In the run-up to the election, Dissanayake repeatedly paid tribute to the Sinhala Buddhist clergy and in an address to over 1,500 Buddhist monks in Maharagama, he assured them that the Sri Lankan constitution would continue to grant the “first and foremost” place to Buddhism and that it has “divine protection”.

It is a sentiment that is widely shared in his party, with senior members such as K D Lalkantha openly associating with racist figures such as the Buddhist monk Gnanasara of the Bodu Bala Sena (BBS or Buddhist Power Force).

Opposed to the devolution of powers to Tamils

Whilst touring the Tamil North-East this April, Dissanayake emphasised that he did not come to offer implementation of the 13th Amendment. This constitutional amendment created the system of Provincial Councils, promising greater devolution of land and police powers to a merged North-East.

Dissanayake addresses a Tamil audience in April.

The amendment was enacted in 1987 as part of the Indo-Lanka Accord and has been staunchly opposed by the JVP since its inception. The JVP staged two insurrections against the state in the early 1970s and the late 1980s. The latter of these was chiefly in response to the Indo-Lanka accord and the 13th Amendment which sought to devolve powers to Tamils in the North-East.

“We didn't come here to ask for your vote,” Dissanayake told the Tamil crowd.

“We didn't come here to tell you that we’d offer you the 13th Amendment and you can vote for us in exchange. I didn't come here to offer you federalism so I can ask for your vote. I came here to discuss how we can help Sri Lanka emerge from its crisis.”

“As a political party we strongly opposed the Indo-Lanka Accord decades ago, and dedicated our initiatives to safeguarding Sri Lanka’s sovereignty, at the cost of many lives," said Vijitha Herath of the JVP earlier this year.

“This stance has not changed and will not change,” he told reporters in Colombo. “Throughout the country’s history, we have consistently made decisions to safeguard our territorial integrity, and we stand by that commitment today and in the future. We give our assurance to the people of this country that these principles will not waver.”

In 2015, then-JVP Propaganda Secretary Herath told The Island, "the JVP is against federalism”.

He also spoke out against the merging of the Northern and Eastern provinces, as outlined by the Indo-Lanka accord. “It is the JVP that went before the courts and got an order to demerge the two provinces that had been arbitrarily merged after the Indo-Lanka Accord,” he added, referring to when the JVP filed three separate petitions with the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka calling for the North-Eastern Province to be demerged. The Province was formally demerged into the Northern and Eastern provinces on 1 January 2007. Jubilant JVP supporters lit firecrackers outside the building at the time.

In 2010, Dissanayake himself said the JVP will oppose if a new political constitution devolving powers to the Northern and Eastern provinces was to be created.

His current 2024 manifesto stresses that they will ensure "territorial integrity and sovereignty of the country without compromise".

Pro-war, Anti-Tamil

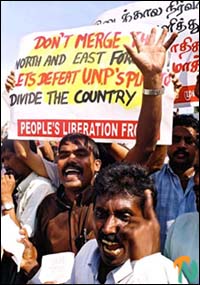

A 2003 anti-peace rally in which Dissanayake participated.

From its inception, the JVP was infused with Sinhala populism and found its support amongst the rural South. Founder Rohana Wijeweera framed Tamil demands for self-determination as in-hoc with US imperialist interests, setting in place a longstanding history of racism towards the island’s Eelam Tamils.

Though the JVP staged two violent insurrections against the Sri Lankan state that saw tens of thousands killed, it found no sympathy or solidarity for Eelam Tamils and instead remained staunchly opposed to Tamil demands for autonomy. The party went on to breed some of the island’s most fervent Sinhala racists.

Dissanayake initially entered parliament via the nationalist list in the 2000 parliamentary election via the nationalist list, a system that sees parties that win a share of the vote awarded an unelected seat.

When a 2002 ceasefire agreement between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and Sri Lankan government was initially signed, Dissanayake was amongst the parliamentarians who fumed against it, telling parliament that ‘the LTTE had laid a foundation to establish a separate state in the island’.

He repeatedly protested the agreement, leading JVP rallies such as the 2003 five-day, 116 kilometres foot march from Kandy to Colombo, demonstrating against the deal.

In 2004 the party’s continued agitation and campaigning explicitly on an anti-ceasefire platform, led to it forming an alliance with the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and allowed Dissanayake to take up a position as the Minister of Agriculture, Lands and Irrigation.

After the devastating Indian Ocean tsunami that year, which saw the deaths of over 35,000 people, two thirds of which were reported to be from the Tamil North-East, the JVP rejected the possibility of joint post-tsunami aid distribution. Instead, the North-East saw vast sums of aid withheld by Colombo.

“We should spit on NGOs and stop them from on our streets. Donor countries and their NGO agents are holding this country to ransom, telling the government to set up a joint tsunami relief mechanism with the LTTE”, Wimal Weerawansa, the propaganda secretary of the JVP told a Colombo audience in April 2005.

The Sri Lankan government faced accusations of using the tsunami as a weapon of war and of denying aid to Tamils. In January 2005, the Sri Lankan government refused to permit the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, to visit the North-East.

Dissanayake and several other JVP parliamentarians would resign from the government a year later, displeased with the ongoing peace process. Instead, his party backed Mahinda Rajapaksa at the 2005 presidential polls, running on a platform specifically opposed to the ceasefire.

In 2006, Dissanayake was present as the JVP launched an organisation known as the “Joint Front to Protect the Nation" to defeat the LTTE and to work for the abrogation of the ceasefire.

As the Sri Lankan government launched a massive military offensive against the Tamil independence movement, the JVP world frequently rally in support of the state.

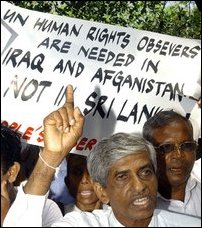

Demonstrations would be held outside Western embassies and the United Nations office in Colombo, as the government repeatedly rejected international human rights monitors.

Anti-peace process protests by the JVP in 2002, 2006 and 2007. (Photographs: TamilNet)

Speaking before military officials in Ratnapura earlier this year, Lalkantha claimed that it was only the JVP, alongside the extremist monks in the Jathika Hela Urumaya (JHU), that enabled for the defeat of “separatist terrorism”.

“Not the SLFP, not the UNP, not the SLPP. Only the JVP and JHU said that we must finish this by war and there is no other solution.”

Vowing to protect war criminals

Aruna Jayasekara.

The Sri Lankan military would go on to kill as many as 167,679 Tamil civilians in a campaign that has been dubbed a genocide. Food and medicine were embargoed, hospitals were repeatedly shelled, widespread sexual violence deployed and surrendering Tamils executed.

The events have been the subject of several UN reports and resolutions, including one that is currently being drafted at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva this month.

The resolutions, and Tamil victims, have demanded an internationalised accountability process to hold perpetrators of war crimes accountable and finally deliver justice for the mass atrocities.

Dissanayake and the JVP have been firmly against such a move, with the JVP leader stating last month he "will not seek to punish anyone accused of rights violations and war crimes".

“Even the victims do not expect anyone to be punished,” he claimed, despite Tamils repeatedly calling for an international accountability mechanism and for Sri Lanka to be taken to the International Criminal Court (ICC).

At the same time, his party has openly embraced military officials implicated in war crimes such as retired general Aruna Jayasekara, reportedly entrusting him with their defence policy. Jeyasekara was the commander of the 3rd contingent to Haiti during a Sri Lankan peacekeeping operation that faced allegations of running a child sex trafficking ring during a UN peacekeeping operation from 2004 to 2007.

A thinly veiled threat?

Last month, a fiery campaign address by Dissanayake sparked criticism, after he was accused of intimidating Tamils in the North-East during a speech in Jaffna. Translated extracts have been reproduced below.

"Jaffna must also be stakeholders of this victory. Do not be labelled as those who opposed this huge change. Be a stakeholder in this change… When the South is gearing up for change. If you are seen to oppose that change, what do you think the mindset of the South be? Would you like it if Jaffna was identified as those who went against this change? Those who opposed this change? Would you like it if the North was identified this way?"

"I assure you again. We will win. But, you must become stakeholders of this victory. Don't be those who oppose it. Ever."

Anti-India?

The JVP has traditionally been thought to have stood on an ‘Anti-India’ platform, having staged the 1987 insurrection, as the prospect of Tamil autonomy in the North-East and the presence of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) stirred up a wave of Sinhalese nationalism.

The party had previously denounced Indian-origin estate workers, Malayaga Tamils, as a “fifth-column instrument of Indian expansionism”. For decades it would rally against perceived Indian expansionism on the island, protesting against deals such as the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), a deal that would open up possibilities for greater trade and investment between the two countries.

Protestors holding placards during a demonstration against CEPA in 2010 (File Photo)

Dissanayake shared those sentiments, telling parliament in 2008 for example that ‘a secret plot has been hatched to hand over Katchatheevu to India’and that it ‘cannot be allowed to succeed at any cost’.

Though the issue of Katchatheevu has been raised by New Delhi in recent months, India also invited Dissanayake for an official tour of the country earlier this year. The visit was seen as a significant outreach by Delhi and marked a possible change of heart from the JVP’s fiercely anti-India rhetoric that came to define its politics.

Dissanayake and a JVP delegation met with politicians, government officials, and members of the business community.

(Photo courtesy: Dr. S. Jaishankar X)

(Photo courtesy: Dr. S. Jaishankar X)

Renegotiating the IMF bailout

After the economic crisis of 2022, under the tenure of then-president Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka has been desperately dependent on a $3 billion International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout package.

The global body has repeatedly cautioned that Sri Lanka’s path to debt sustainability remains ‘knife-edged’.

The IMF’s Communications Department Director, Julie Kozack, said last week that a planned programme discussion will take place before the release of the next tranche of funding, which is estimated at about $350 million.

But Dissanayake has repeatedly said that his party would seek to “re-negotiate” the terms of the agreement, something that the current government has warned against.

Sri Lanka’s State Finance Minister, Shehan Semasinghe warned of an imminent economic collapse if parliament is dissolved and a third review of the much-needed IMF loan is not completed.

Semasinghe stressed that abandoning the deal would jeopardize Sri Lanka's recovery, potentially dragging the country into a crisis similar to the one it faced in 2022. “We must adhere to what we have agreed. We cannot unilaterally deviate from the program, as that would effectively mean walking out of the agreement,” Semasinghe told reporters during an event in Colombo.

“If that happens, Sri Lanka could easily return to the conditions we faced in 2022.”