With Sri Lanka’s presidential hopefuls tussling to announce their candidacy this week, there was a familiar name back in the headlines - Rajapaksa. The latest candidate in the lineage, Namal, the son of the former president who oversaw the slaughter of countless Tamils, has formally been put forward to stand by his ultra-nationalist party backers. Though the polls are still some weeks away, the return of the family to the very frontline of Sri Lankan politics is a chilling reminder that Sinhala Buddhist chauvinism remains deeply embedded into the island’s politics. And so too are the Rajapaksas.

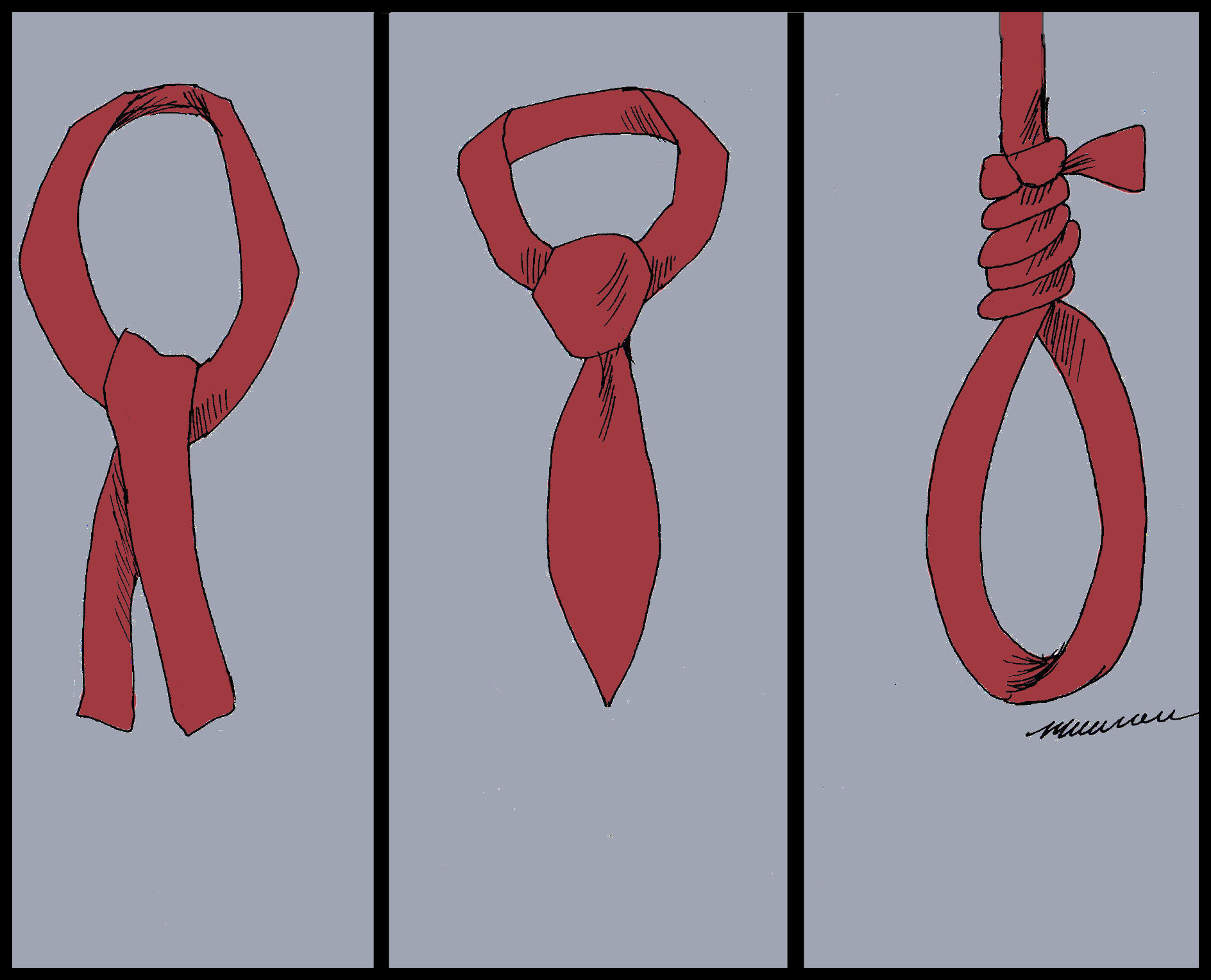

Illustration by Munaa.

With Sri Lanka’s presidential hopefuls tussling to announce their candidacy this week, there was a familiar name back in the headlines - Rajapaksa. The latest candidate in the lineage, Namal, the son of the former president who oversaw the slaughter of countless Tamils, has formally been put forward to stand by his ultra-nationalist party backers. Though the polls are still some weeks away, the return of the family to the very frontline of Sri Lankan politics is a chilling reminder that Sinhala Buddhist chauvinism remains deeply embedded into the island’s politics. And so too are the Rajapaksas.

The announcement of Namal Rajapaksa as a candidate comes just two years after his uncle Gotabaya Rajapaksa was unceremoniously run out of power. Protests swept through Colombo and through the president’s personal residence in 2022, as anger over corruption and economic mismanagement forced Gotabaya to flee. But the potential return of yet another member of the Rajapaksa regime demonstrates the deep seated failure of the ‘aragalaya’ protests to make any meaningful impact. Indeed, any hope of change was quashed within just a few weeks when Wickremesinghe, a close ally of the Rajapaksas, took charge as Sri Lanka’s president. The mass protests that shook the streets of Colombo were quelled and normal programming resumed.

Namal Rajapaksa, who is controversially linked to the murder of rugby player Wasim Thajudeen, has politics that bear little difference to that of his father or uncle. Both Mahinda and Gotabaya directed the worst mass atrocities that the island has ever seen, as they carpet bombed and massacred tens of thousands of Tamils in 2009. They are both war criminals. Namal has unsurprisingly said little about holding either of them to account, or on delivering justice that Tamils have fervently demanded. Instead, his party has pursued staunchly Sinhala extremist policies, whilst courting racists and human rights abusers.

These are commonalities shared amongst almost all the Sinhala candidates in the South. The main opposition parties have also recruited former military figures, including those responsible for war crimes, into the fold. Not a single candidate has spoken about an international criminal tribunal to ensure accountability for the atrocities. None have promised to halt the ongoing construction of Sinhala Buddhist monuments across the Tamil homeland. Neither have they pledged to respect Tamil demands for self-determination or to end the military occupation. As we have stated previously, Tamils see nothing to gain from engaging in these elections or in Southern party politics.

The Rajapaksas toxic brand of Sinhala chauvinism is not new. They are just one, particularly brash, manifestation of the Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism that has been the central driver of Sri Lanka's politics since independence. What is particularly telling about the return of a Rajapaksa candidate, however, is how lasting the family’s popularity is amongst the Sinhala south. Indeed, it seems that despite the Rajapaksa record of corruption and economic disaster, one that has directly and only recently destroyed the livelihoods of Sinhala voters, their politics remains gripping. The Sinhala electorate will still give space to those who espouse the most extreme and brutal form of chauvinism they desire.

With a continuation of almost 20 years with a Rajapaksa at the polls, it is clear the dynasty is looking to cement itself. Without changing the system that allowed figures like the Rajapaksas to rise to the all-powerful positions that they were in, the same cycles of illiberal, ethnocratic and unaccountable rule, are doomed to repeat themselves. Unfortunately, the upcoming polls will do little to bring about that desperately needed reform, no matter who comes to power. Instead, as the Tamil people have known for decades, it is in the capitals around the world and through international action that change will come.