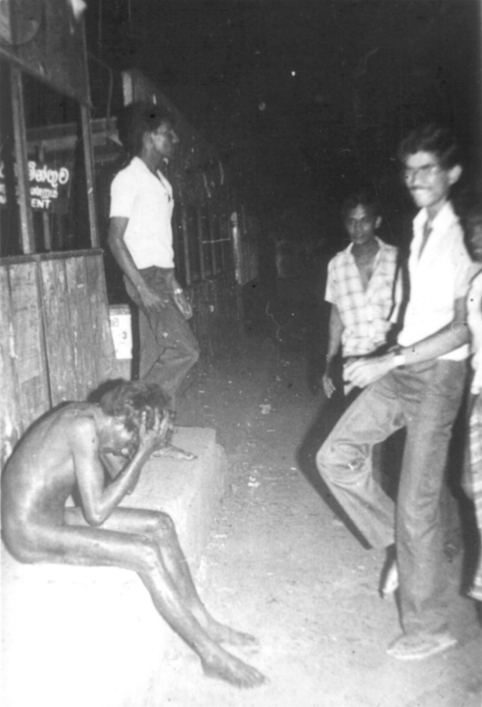

Naked and bloodied, the exhausted youth slumps on a bench by the filthy roadside, his head in hands, awaiting the final blows.

His casually dressed pursuers gather round. One be-spectacled young man grins as he raises his right knee in preparation for another blow.

This single image, above all others, has come to represent the traumatic events of ‘Black July’ 1983 for Sri Lanka’s Tamils.

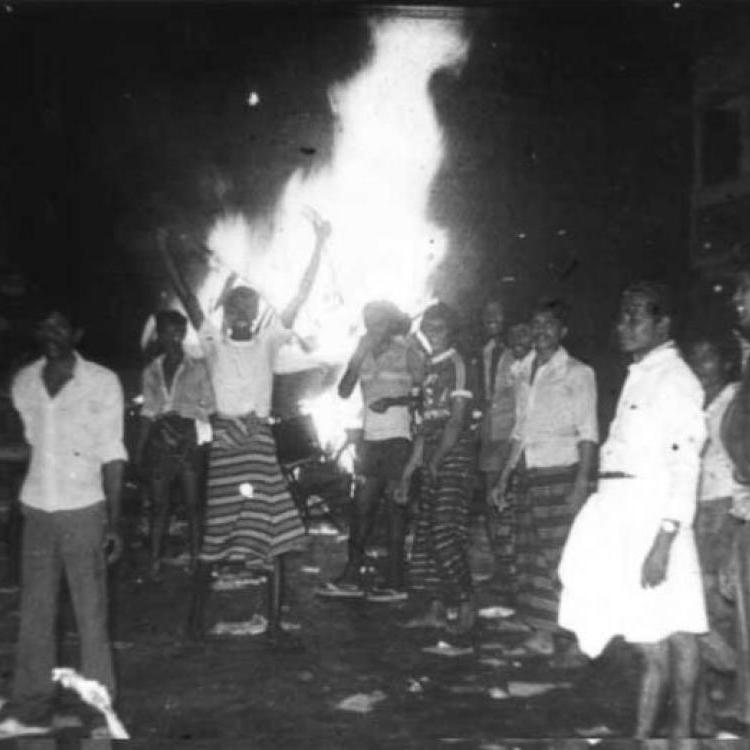

The mayhem that erupted across Colombo and other parts of the south when state-backed mobs of rampaging Sinhalese attacked Tamils and their property might seem distant from the now iconic image of the lone victim surrounded by a small group of laughing, even bored, slightly built youth.

Over 3,000 Tamil people were killed in over 6 days of organised anarchy between July 24-30 1983 (the official government figure for the deaths was 358).

The pogrom, organised by Sri Lanka’s state forces and carried out by Sinhala mobs targeting Tamils from voters’ lists made available to them entered Tamil consciousness as ‘Black July’ or ‘the Holocaust.’

But the image of the lone Tamil boy cornered by a group of Sinhala youth touched a nerve in a minority community feeling beleaguered and utterly defenceless as the majority community and the state turned on them.

‘Black July’ triggered a flood of recruits to a myriad of Tamil militant groups, including what has now became a standing army, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

Many commentators have thus erroneously linked the July 1983 (and an ambush by Tamil fighters which killed thirteen soldiers which is cited as the ‘reason’ for the riots) to the start of the conflict.

In fact Tamil militancy began in the mid-seventies, but it long remained a shadowy phenomena, eclipsed by (though undoubtedly nurtured in) the mass mobilisation behind the parliamentary Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF)’s non-violent drive for independence for the discriminated Tamils.

Amid the tumultuous changes that have gripped Sri Lanka in the near quarter century since July 1983, that iconic photograph has endured, the moment of racist violence it captures a potent reminder to the Tamils of their vulnerability.

The photograph itself was taken by Chandragupta Amarasinghe, working for a Communist newspaper at the time.

Although fearful of the consequences of photographing the state-backed rioters, Amarasinghe and a colleague decided to try anyway. As the Sinhala youth closed in on the Tamil victim, they seized a chance.

Amarasinghe whipped the camera up, snapping a frame before tossing it into an open bag being held open by his friend. They then fled. In the bag was a captured moment of Sri Lanka’s violent history. It is doubtful they were even aware of its potency.

The photograph is made /p> available to Tamil Guardian by the well-known Australia-based academic Michael Roberts,who later acquired it from Amarasinghe.

_____

This article was originally published in July 2006.