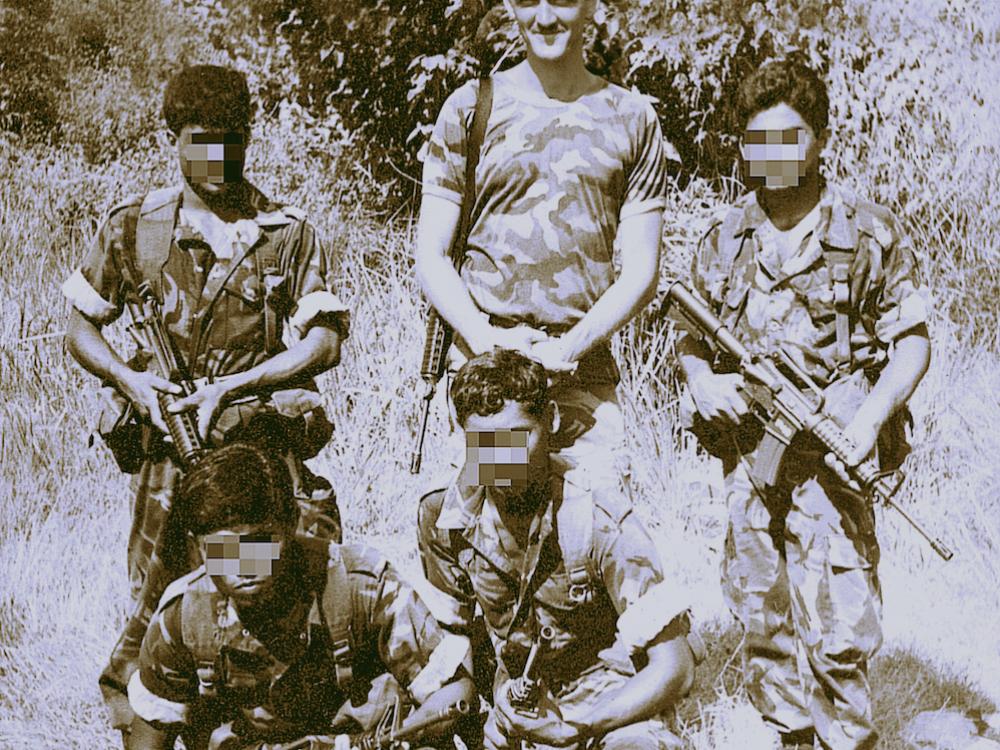

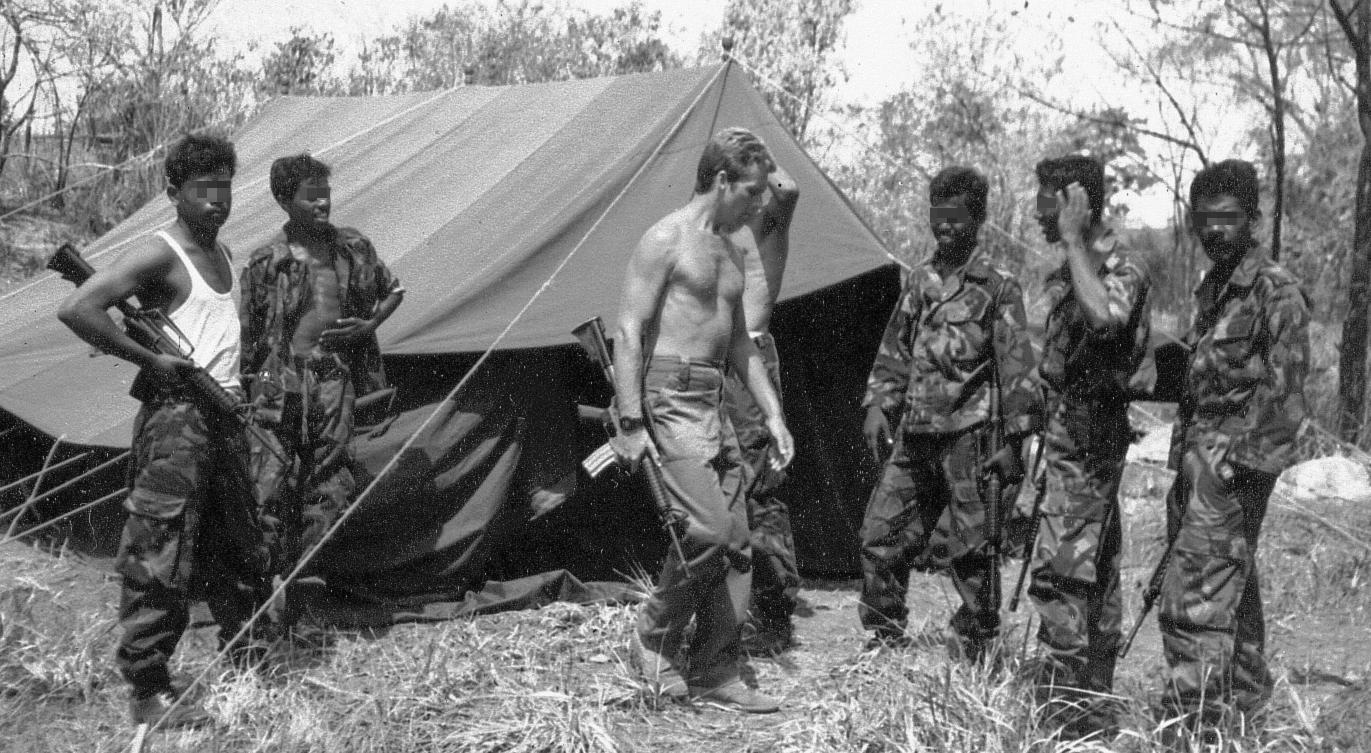

Reporting in Declassified UK, journalist Phil Miller, reveals attempts by one of Britain’s oldest private security companies, Saladin, to distance itself from a mercenary organisation known as Keenie Meenie Services (KMS) which is currently being investigated by the Metropolitan Police for war crimes committed in Sri Lanka during the 1980s.

According to Miller, not only did Saladin share an office building with KMS in west London but many of in senior staff held positions in both companies. KMS’s co-founder, Major David Walker, worked as a director of Saladin whilst working for KMS and is still listed as a director for Saladin under Companies House records.

Walker, a former officer in the British Special Air Service, oversaw a contract in which KMS pilots were alleged to have massacred Tamil civilians on behalf of the Sri Lankan government. KMS was eventually dissolved in 1988.

Read more here: ‘Lifting the mask on British duplicity’ - Interview with Phil Miller

He is also accused of leading operations in KMS in conjunction with US marine Colonel Oliver North and the Contras to covertly overthrow the democratically elected Sandinista government in Nicaragua. In March 1987, the US Congress heard testimonies on this issue, with Walker specifically being implicated in the bombing of a hospital in the capital Managua.

(Photo of Archie Hamilton)

Both KMS and Saladin have longstanding connections with the UK government. Miller notes that “former Conservative defence minister Archie Hamilton, who served from 1986-93 under prime ministers Margaret Thatcher and John Major, became a director of Saladin a few months after leaving the government”. KMS is also known to have former SAS soldiers and to have provided security services for the UK Foreign Office.

Saladin’s response

Despite the closeness between the two organisations, Saladin has told the UN Working Group on Mercenaries that whilst the two firms “ran side-by-side for a time” they undertook “entirely different tasks”. Saladin claimed to focus on protection against “kidnap and ransom” while KMS “by contrast provided military or paramilitary training and personnel”.

However, government files have shown that KMS also undertook significant bodyguarding services, with Walker personally managing KMS contracts to guard European officials in Uganda and British diplomats in Argentina.

According to complaints filed by European officials in the 1980’s, KMS staff were “useless” at enforcing discipline on their Ugandan contract, with the result that KMS men had been involved in “several major car accidents, drunkenness, etc.”

Whilst Saladin has tried to distance itself from KMS, the UN’s Working Group on Mercenaries has expressed concern over Saladin’s website which stated, Saladin, with its predecessor KMS Ltd, has provided security services since 1975”. This claim was displayed on Saladin’s website for seven years from 2011 until 2018.

Saladin claimed to the UN experts that this “was a marketing stratagem and is inaccurate”, claiming it was “explained by a measure of poetic licence on our part”. Miller writes that whilst Saladin is now trying to distance itself from KMS, the company told the UN that the statement on its website “was probably drafted with the objective of garnering some of KMS’s successes for Saladin’s subsequent benefit”.

KMS’s training of Sri Lanka’s STF

In a 2017 letter written by Walker to the head of Sri Lanka’s police Special Task Force (STF), he states;

“It continues to be a matter of great pride that I frequently heard STF described as the most effective force in the country. [At that time we operated as KMS Ltd – Saladin Security is its successor company].”

According to criminologist Dr Rachel Seoighe, a consultant for the Tamil Information Centre,

“Walker proudly announced that Saladin is KMS’s successor company in private correspondence to Sri Lanka’s brutal Special Task Force; this is now being publicly denied because it may have reputational and legal consequences – including allegations of war crimes committed by KMS, the company he co-founded and in which he played so intimate a role in Sri Lanka and elsewhere.”

“Saladin can’t have it both ways: claiming the ‘successes’ of KMS while distancing itself from atrocities linked to the company”, she added.

Miller notes that “KMS trained the STF from scratch during the 1980s”, with the unit becoming increasingly “involved in disappearances and massacres of Tamil civilians the longer the training went on”.

According to a CIA assessment of Sri Lanka from 1986, “the STF’s superior combat performance relative to the army is due to its KMS training… a common STF tactic when fired upon while on patrol is to enter the nearest village and burn it to the ground”.

Currently, Saladin operates in Ghana, Kenya and Afghanistan, but they assure the UN that Saladin has “never been the subject of any investigation or enquiry regarding human rights violations”.

Saladin further acknowledges that Walker worked for KMS and their own company but denies that he was the director of KMS. They further maintain in a letter to the UN that “all the key UK figures from that time who were shareholders and/or directors of KMS are now dead.”

This claim is rebuked by Miller who maintains that whilst the chairperson, Colonel Jim Johnson, died in 2008, “the people Walker worked within the 1980s were under the impression that he held a very senior position at KMS”.

Dr Seoighe similarly remarks that;

“Walker’s fingerprints are all over the company’s history. Claiming that all KMS’s senior figures are now dead is an attempt to shut down legal avenues of accountability, which – because of the Metropolitan Police war crimes team investigation – may now be on the horizon.”

Voluntary accords

Saladin has claimed that it is adhering to the 2008 Montreux Document and was a founding member of the International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA). These are voluntary codes to promote “the responsible provision of private security services”, and the ICoCA website makes clear that it “creates no legal obligations and no legal liabilities for companies”.

Miller notes that this “form of industry self-regulation” came about as a result of powerful countries resisting an international ban on mercenaries. This was considered in the 1980s at the UN while KMS was fighting in Sri Lanka. Britain’s top diplomats at the UN in 1989 regarded the proposed ban as acceptable for it would only hinder mercenaries involved in “nefarious activities such as a coup”.

The decision to endorse the ban was entrusted to three of Thatcher’s cabinet officials, including armed forces minister Archie Hamilton, who went on to become a director of Saladin.

Whilst Britain never signed the UN treaty, the UK Foreign Office has promoted voluntary initiatives such as ICoCA. Miller notes that the Foreign Office’s Responsible Business Team discussed Saladin “informally” with ICoCA before writing to the group in July to “better understand… the due diligence process” applied to Saladin’s membership.

Read more at Declassified.