Descendants of victims of the genocide in Namibia have called on Germany to “stop hiding” and discuss reparations with them directly, as they take their own government to court for making a deal without their approval.

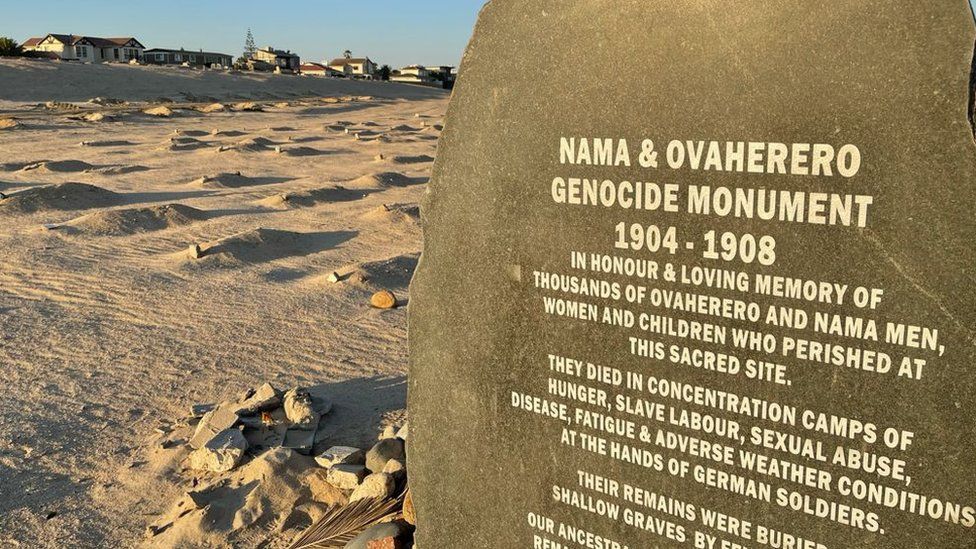

The Herero and Nama people have gone to Namibia’s high court, rejecting an apology made in 2021 after years of talks between Namibia and Germany, which they say falls short of atoning for the 1904 to 1908 genocide, the first of the 20th century.

“We were not involved at any stage. The government set the agenda, it discussed what it discussed and never disclosed it until we saw a joint declaration last year,” said Prof Mutjinde Ktjiua, chief of the Herero.

The declaration included a German pledge of €1.1bn (£980m) in development projects over 30 years but Ktjiua said the tribes want direct reparations to address the poverty and marginalisation that resulted from the genocide.

The German empire unleashed a campaign of killing and torture after the tribes rejected colonial rule in 1904. An estimated 80% of all the Herero people and 50% of Nama were killed; estimates vary between 34,000 and 100,000 people. They are now politically marginalised minorities in Namibia.

A spokesperson for the German foreign office said only the Namibian government had the mandate and “democratic legitimacy” to negotiate with Germany, but the federal government had sought the voices of the descendants of victims, including through an advisory committee of five people who worked with the Namibian negotiator, who was himself Herero.

“The federal government calls the crimes committed against the Herero, Nama, Damara and San by their name: genocide. The fact that we use this term in its historical rather than its legal sense is because the Genocide Convention of 9 December 1948 cannot be applied retrospectively,” the spokesperson said.

Karina Theurer, an adviser to the Namibian lawyers, said Germany has argued against responsibility, referring to the historical legal position when European powers distinguished between “civilised nations and the savage or wild nations”.

“You cannot today rely and base your legal arguments on such a racist distinction,” she said, adding that the case could “open the floodgates” for other former colonies to demand reparations against occupying powers.

Read more at the Guardian