|

Amid the deepening violence in the Sri Lanka, it was merely to be another round of shuttle-diplomacy, to 'sound out' President Mahinda Rajapakse's administration and the LTTE. But something very different to routine happened this time.

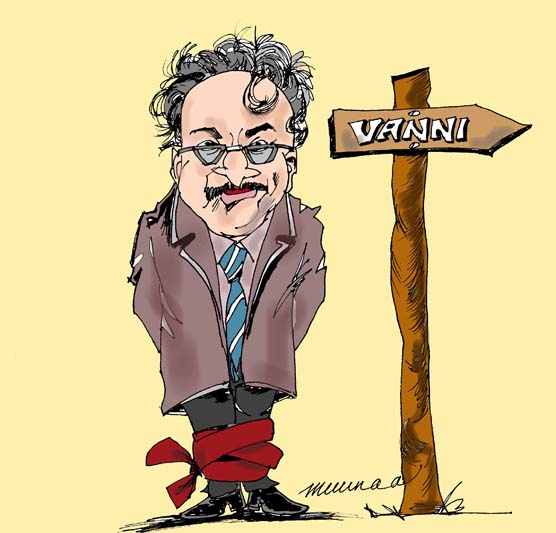

When he met government officials, he was given a blunt directive: he was not to go to Kilinochchi to meet the LTTE until the government granted him permission. The hapless envoy cooled his heels in Colombo and waited.

He eventually went to Kilinochchi - empty handed. He returned empty handed too.

But something crucial had happened. By agreeing to the government's terms for Norway's involvement in peace efforts, Mr. Hanssen-Bauer had compromised Oslo's 'third party' neutrality. More importantly, Oslo's prestige as a respected actor on the international stage had been dulled.

In short, his curt order to stay put was a humiliation for an international diplomat fronting not only Norway but the collective international community involved in Sri Lanka's peace process - i.e. the Co-Chairs.

The neutrality of the third party is sine quo non for peace making. At the outset, despite the international intrigue in Sri Lanka, Norway treated both parties equally in the peace process and, equally importantly, was treated with dignity and respect by the parties to the peace process.

Interestingly, throughout the peace process there has never been friction - at least publicly - between the LTTE, the armed non-state actor, and Norway, frontsman for the international (state) system.

There have been periodic bouts of friction between the Sri Lankan state and Norway. Apart from the embarrassing and now infamous 'salmon-eating busybodies' incident, there were (unsuccessful) demands that then Special Envoy Erik Solheim be replaced.

These frictions were mainly with President Chandrika Kumaratunga's office and later administration. The market friendly - and Sinhala conservative - UNP got on famously with the Norwegians.

But even the moments of friction did not involve official attacks on Norway's integrity or those of its personnel by the Sri Lankan government.

But that was before President Mahinda Rajapakse came to power on a surge of Sinhala-nationalist support. As he made clear last week, their mandate, as he sees it, is to 'defend the motherland.'

From the outset, President Rajapakse made it clear he did not value the Norwegian help. He claimed he would solve the problem if could talk directly with Mr. Pirapaharan.

Dismissed by everyone as a political stunt or mere rhetoric, the underlying corollary was ignored: just as he had promised in the election manifesto that proudly bears his personal stamp of ownership - 'Mahinda Cinthanaya' - he intended to end Norway's involvement.

Why would the President, inheriting a country riven by renewed violence drive out a key international ally in peace building? Because President Rajapakse wants 'peace with dignity' - by which he means the restoration of Sinhala hegemony and an end to upstart Tamil aspirations.

In short, he wants to destroy the LTTE miltiarily.

The first step to doing that is to isolate them from the international community which, in his view, has given too much emphasis to the Tigers' opinions and demands.

And the first step to isolating the Tigers is, in his view, to get rid of Norway or at least replace her with a more appropriate interlocutor - i.e. one that is hostile to the LTTE.

Indeed, President Rajapakse didn't even mention Norway in his inaugural address as President in November 2005 - though he went through a range of international 'alternatives' to Norway.

President Rajapakse began his unstated, but discernible plan at once. In December he turned publicly and pointedly to India for help with solving the ethnic question.

The move failed. Not only was India unfavourable to replacing the Norwegians, an alarmed Delhi could see what many other internationals did not: Rajapakse was not intent on a negotiated solution but was instead preparing the military option.

With Delhi's involvement not forthcoming, President Rajapakse had to find an alternative way of removing the Norwegians.

He did not wish to simply tell them to get out: they could take much international goodwill and not a little international aid with them.

However, if he couldn't ask them to go, he could certainly make it impossible for them to stay.

One thing President Rajapakse was sure of is that his efforts to eject the Norwegians would draw considerable support from the Sinhalese. (It is no accident that not once has the UNP, despite its closeness to Oslo, ever publicly defended the Norwegians' efforts).

Notwithstanding claims of a 'peace constituency' in the south, the insidious campaign run by the ultra-Sinhala nationalists such as the JVP, JHU and PNM - assisted by the regular criticism by President Chandrika - had laid the groundwork for President Rajapakse.

Numerous protests outside the Norwegian embassy - often accompanied by the torching of the Norwegian flag - had already muddied Oslo's standing such that even very public sponsorings of Buddhist temples in the south could not fix. (Even Norway's offers to discuss their role with the JVP only lent weight to the latter's disdain for Oslo.)

When the February 2006 peace talks were agreed to, amid fast rising violence, the LTTE suggested the talks could be held in Oslo. President Rajapakse refused.

His opting for Geneva (disregarding an earlier demand any more talks must be within Sri Lanka itself) was not so much about contradicting the LTTE (as was commonly understood) as snubbing Norway.

The peace process stalled: the Geneva I agreement on paramilitaries became a laughing stock, violence escalated.

But it was the proscription of the LTTE by Canada and the European Union that fast tracked President Rajapakse's plans. If the original plan was to eject Norway to isolate the LTTE, particularly from the EU, then the wider objectives had unexpectedly come about anyway.

The urgency to eject Norway thus eased temporarily. Now it was a question of stepping up military operations (particularly in the east) and destroying the peace process by escalating the conflict.

The objective of marginalizing Norway remained. In July President Rajapakse sent a personal message to the LTTE to talk directly. It was conveyed by N. Vithyatharan, the editor of the Jaffna daily, Uthayan.

"If the LTTE and the government can agree to put an end to all violence for two weeks, [we] could make a fresh start and develop the rapport from there on. We don't have to do it through Norway or be dependent on them, we can deal directly," the paper quoted Mr. Rajapakse as asking Mr. Vithyatharan to tell the Tigers.

But the LTTE rejected the notion, insisting Norway remains as facilitator.

In July the Sri Lankan government even agreed to hold talks in Oslo. But the July 'meeting' - in which Norway unilaterally invited the government and the LTTE - turned into a fiasco.

The government sent a non-delegation comprising relatively junior officials. The LTTE said it came to meet with Norway, not Sri Lanka.

Piqued by the LTTE, Norway held very public meetings with top Sri Lankan officials - even the King of Norway met Sri Lanka's Foreign Minister.

But whilst this did not make Colombo any more amenable to Norwegian's continued role, it boosted Sinhala nationalist haughtiness about the 'white Tigers.' Meanwhile, another Norwegian-wielded thorn in President Rajapakse's side was the international ceasefire monitors' presence on the ground.

Twice now the Rajapakse administration has tried to compel the SLMM to pull out of its own accord - by firing artillery barrages at SLMM chiefs when they meet with the LTTE.

The first was in July at Maavil Aru and the second time was in Pooneryn in November.

With neither the Norwegian diplomats nor the ceasefire monitors they appointed showing any signs of leaving, the campaign against them has escalated.

When he met Indian Premier Manmohan Singh in November, President Rajapakse didn't disguise his wish to see the Norwegians depart. His very public grumble makes it clear: 'the unwelcome Norwegians are in our house; if only they would go.'

It was the state-owned Daily News which published allegations of financial dealings between him and the LTTE. The shocking claims compelled the Norwegian government to issue an angry denial - and this week even the main opposition in Norway felt it had to come out and back Mr. Solheim.

Sri Lanka's vice-like control of state media is well known, and particularly the mass- circulating English language Daily News would not have printed the story without either receiving official sanction or being sure it would get it.

Indeed, President Rajapakse's administration is yet to apologize for making the allegations - and the Daily News is yet to distance itself from them.

It is in this humiliating context that Mr. Hanssen-Bauer arrived in Sri Lanka last week, to be treated, not as a key international figure, but an interfering busybody.

In the past a visit by Norwegian Envoys, even when 'routine', drew considerable interest within Sri Lankan and abroad - a quick stock take and return would sometimes invoke lurid media headlines of diplomatic 'failure.'

Ironically, it is Norwegian persistence with the peace process in Sri Lanka is likely to draw more and more public slaps in the face from the Rajapakse administration.

And it is not simply a question of Norwegian prestige in the Sri Lankan context, but globally.

In the meantime, Sri Lanka's undeclared war continues at all the intensity of the late ninties.

But, as President Rajapakse intended, it is Oslo which may finally pull the plug on the Norwegian peace process.