Based on leaked extracts, the UN expert panel’s report on Sri Lanka constitutes a watershed moment in international understanding of the crimes committed in the closing phase of the war in Sri Lanka.

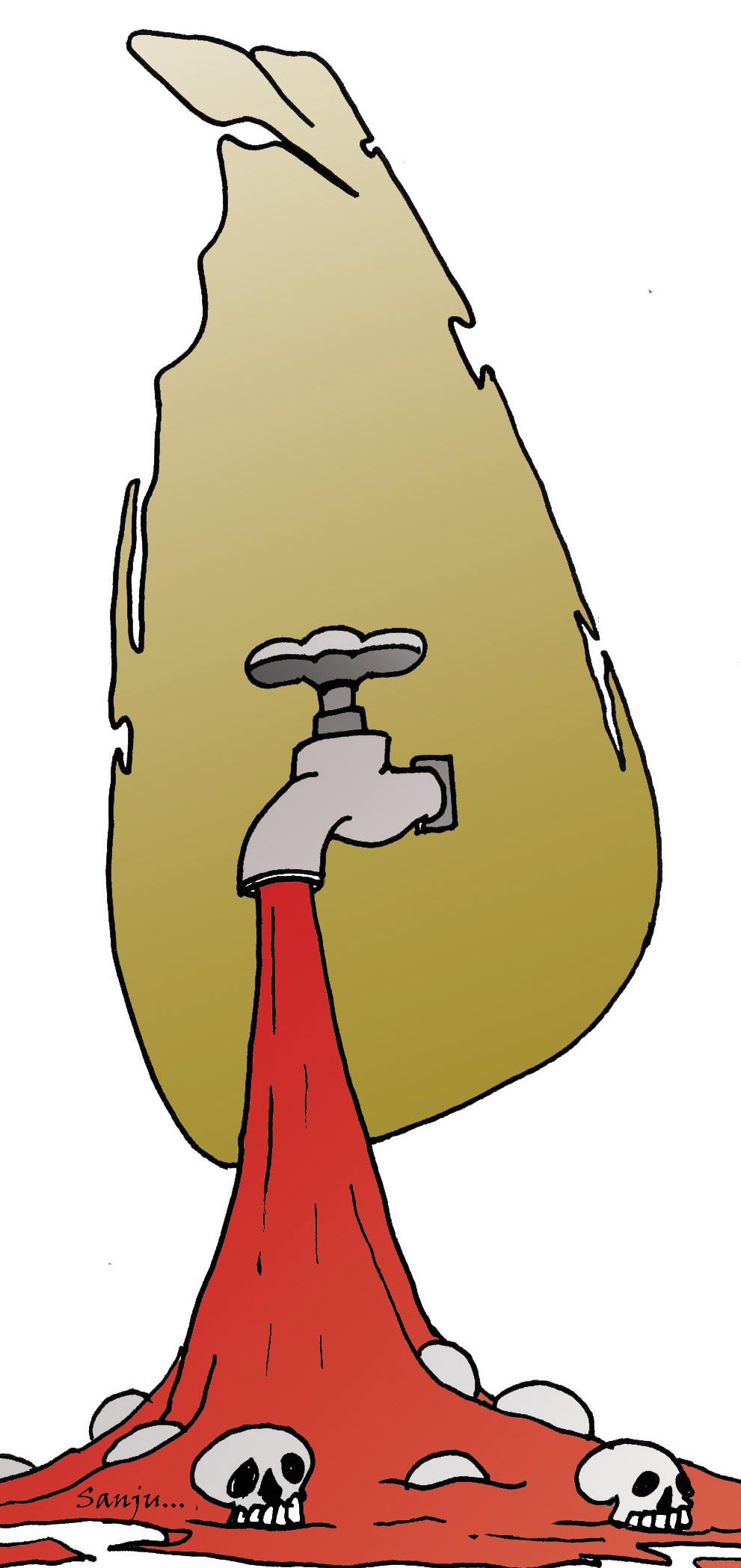

Crucially, although the word does not appear in the extracts, the report’s contents well supports the charge that Sri Lanka engaged in genocide of the Tamils. The report lays out in detail the calculated, deliberate and systematic targeting of Tamil civilians by the Sri Lankan armed forces, operating under the direct command of the country’s top political leadership.

The former UN spokesperson in Sri Lanka, Gordon Weiss, has aptly termed the publishing of the UN experts’ report as a ‘Srebrenica’ moment for Sri Lanka and indeed for the world.

The analogy is correct on many counts. Firstly, it was in relation to Srebrenica that the ICTY (International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia) most clearly formulated the principle that part destruction – specifically, a geographically contained (i.e a small territory) destruction - of an ethnic or national group constituted genocide.

Deaths and more

The ICTY held to be genocide the systematic executions of an estimated 8,000 Bosnian men and boys -or 1 in 5 - out of a population of 40,000 (the target group) in Srebrenica, and a total population of 2 million. However, the now well substantiated allegations against Sri Lankan state and the Rajapakse regime are an order of magnitude greater.

The UN expert panel finds that a credible estimate of civilian deaths in the Vanni would be 75,000 (or nearly ten times Srebrenica’s grim total) from an estimated population of 330,000 Tamils (or 1 in 4 of the target group), out of a total population of 3 million Tamils in Sri Lanka.

The report also estimates the ratio of physically injured to dead as 1:2 or 1:3, and says the number killed could be much higher. It notes that approximately 40,000 surgical procedures and 5,000 amputations were carried out on the wounded, under horrific conditions.

The genocide convention, of course, covers not just killing but serious physical or mental harm. And the UN experts’ report goes on to provide harrowing details of the subhuman medical and humanitarian conditions the Sri Lankan state created for the Vanni population, surrounded by its armed forces, by withholding food and medical supplies and relentless bombardment for months on end.

Deliberate, systematic, widespread

|

As genocide experts recognize, it is not necessary to have explicit or recorded statements of intent to destroy or indeed explicit orders to this end. For example, not even the Nazis left a traceable trail of explicit orders for the various forms of destruction of their target groups. Intent can be inferred, often where no other plausible explanation is possible.

To return to Srebrenica, it is not the numbers that make the comparison valid. Indeed, the Rajapaksa regime seems to have adopted the modalities of the Serbian genocide.

Srebrenica was also a designated a safe haven (by the UN), encouraging civilians to concentrate there, and thereby making the mass killings possible. As the UN experts’ report notes, in Vanni, the Sri Lankan state three consecutively times declared ‘No fire Zones’, thereby encouraging civilians to concentrate there, before unleashing its mass bombardments.

The charge of genocide against the Rajapakse regime is simply this: that from the outset, it intended to substantially destroy the target group, namely the Tamils in the Vanni, and to ethnically cleanse the region in such a way that the community living there would not be able to be ever reconstituted in its original form.

Selected site

The ICTY found that the Srebrenica was chosen for its cataclysmic destruction because of the location’s strategic significance for the viability of the Bosnian state. As the ICTY’s 2004 report (p6) found, “capture and ethnic purification of Srebrenica would therefore severely undermine the military efforts of the Bosnian Muslim state to ensure its viability.”

Similarly, Sri Lanka marked the Vanni for a hammer blow because of its symbolism as a Tamil heartland and its strategic significance for the viability of a Tamil state. In a continuation of this logic, two years after the war ended, the vast majority of returning Tamils live under tarpaulins and corrugated sheets, while the Sri Lankan military sets up increasing numbers of bases and camps and, in parts, settles Sinhalese.

Crucially, the ICTY found that Serbian forces decided that “the elimination of the Muslim population of Srebrenica, despite the assurances given by the international community, would serve as a potent example to all Bosnian Muslims of their vulnerability and defenselessness in the face of Serb military forces.”

Similarly, the Sri Lankan state sought to deal the Tamil people such a traumatizing blow that they would no longer challenge Sinhala dominance of the entire island. As President Rajapaksa declared afterwards, the idea (of an independent Tamil Eelam) that began at Vaddukoddai in 1976 had been ended at Mulliyavikal in 2009.

Realisation dawning

While the UN experts’ report has not labeled what it oulines as genocide, it is clearly cognizant of the presence of the necessary indicators; the report is unequivocal that “[Sri Lanka’s] campaign constituted persecution of the population of the Vanni.”

Genocides do not occur outside of historical context and a prevailing racism. As many historians note, the Nazis’ extermination of Jews occurred amid the latent anti-Semitism in Europe of that period, and prior centuries of persecution.

The UN experts’ account of the events of 2009 have to be located, therefor, in their proper historic and contemporary trajectory. In successfully killing1 in 4 of the people of Vanni, the Rajapakse regime was continuing long-running trends of ethnic cleansing and annihilitary persecution undertaken by earlier governments.

As such, it is not the recognition of Vanni as Sri Lanka’s Srebrenica moment that is so surprising but the fact that this took so long to happen.