Sri Lanka’s rhetoric on the urgent need for development in the Northeast belies its systematic efforts to disrupt the Tamil people’s recovery and subvert international assistance towards further consolidation of Sinhala dominance over them. The state’s cynical calls for the international community and the Diaspora to contribute to development of the Northeast must be viewed against its actual practices and past record.

Despite making much of the desperate humanitarian needs of the people in the Northeast, the state is actively throttling any international efforts to assist. Visa restrictions and severe operational limits, including access, are imposed on international NGOs seeking to work in the Northeast. The ICRC and key UN agencies have been ordered to drastically reduce their presence in the Tamil areas.

Controlled halt

Even India’s ambitious proposed 50,000 housing scheme for displaced Tamils has run into ministerial interference and bureaucratic resistance. The Minister of Economic Development Basil Rajapakse has ordered that “no new buildings should be constructed under donor-funded loan and/or grant project” in the Tamil areas. The powers of local authorities such as Jaffna Municipal Council and Eastern Provincial Council (which in any case are staffed by pliant government loyalits) have had their powers brought under the remit of the Urban Development Authority which, as of May 2010, comes under Sri Lanka’s Defence Ministry, no less.

Overall, development in the Northeast has been brought under strict state control, and thus to a halt - except for specific projects to advance and cement Sinhala dominance over the Tamil areas. Military fortresses are being expanded and Sinhala settlers brought in with state funding, direction and protection. Emblematically, the state is building new Buddhist temples whilst Tamil places of worship remain in ruins.

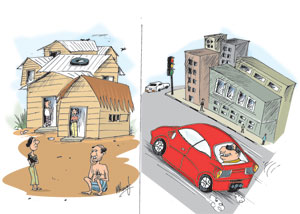

At the same time the hundreds of thousands of Tamils whose lands were forcibly appropriated by the state under the catch-all explanation of ‘the war’ languish in poorly served camps or build shacks in places they have been dumped – ‘resettled’. The ‘lucky’ few rely on relatives’ goodwill and charity.

|

| North and South. Cartoon Sunday Times (SL) |

Historical practice

Moreover, these discriminatory practices are not new. Long before the armed conflict began, the state was concentrated its developmental efforts on the Sinhala South. Colombo was not always the most developed part of the country- as visiting Indian Foreign Minister S M Krishna pointed out last month, Jaffna was historically a centre of regional trade. It took state policy after independence to disrupt and change this.

Using the armed conflict as pretext, the state imposed strategic restrictions which stifled key Tamil industries – particularly farming and fishing. It appropriated international aid - from 1977 until recently, Sri Lanka was the largest per capita recipient of international aid in the world - to deliberately economically advance the south at the expense of the Northeast.

Jaffna still lies in ruins – even though Sri Lanka elaborately celebrated its capture fifteen years ago – while industry has been actively developed in the south. Despite the state's 2007 theatrics of ‘Eastern Revival’ the Tamil areas there remain as destitute and militarised as at any time in the war.

Deadly indifference

The state’s actions after the December 2004 tsunami exemplify its institutionalised racism. For days after the disaster, no government aid was sent to the Northeast, and little thereafter – as aid workers, international media and donors’ own accounts attest. Italian officials escorted their aid in desperation. International aid groups and the Diaspora sent collections of food and medicine to their people – but the shipments were either blocked or looted in Colombo’s port. (see for example, reports in Feb, May, and August 2005). The Tamil areas recovered to some extent only when international actors began working directly with Tamil actors on the ground, including the LTTE, and when Diaspora funding and volunteers flowed their homeland (see p6,12 and 20 here).

The world gave generously to Colombo - which spent it largely on the South, and for purposes unrelated to the tsunami (see studies from 2007 and 2009). Three years after the tsunami, whilst house rebuilding was advanced in the south, it had not even started in government-controlled parts of the Northeast.

Ingrained

The international community is today urging a ‘political settlement’ and ‘devolution’ to allow non-Sinhala regions the political and economic wherewithal to recover and rejoin the modern world – an ambition for which both international and Diaspora assistance will not be lacking. It is no surprise the state is deliberately ignored these calls and chanting a hollow mantra of ‘development’ instead. Infused with a Sinhala supremacist logic, it is fanatically opposed to both power-sharing and Tamil economic recovery.

Sri Lanka cannot be seen as a developing state seeking to do advance the wellbeing of its collective population. Rather, it is an ethnocracy seeking to cement in political, economic and territorial terms, a hierarchy of Sinhala over the non-Sinhala. The point will become abundantly clear in the immediate future. The question then will be, how a just peace can be brought about, and Tamil progress made no longer hostage to state racism.