|

When ratings agencies upgraded Sri Lanka’s debt rating – to still well below ‘investment-grade’- late last year they added a warning: the government needs to demonstrate a commitment to fiscal discipline and cutting its deficit to keep these ratings.

However, despite solemn promises – including those in the November budget – of economic reforms, the Sinhala-nationalist government is unwilling to abandon the populist measures on which both its electoral support and its ethnicised vision of the economy rest.

These are the stakes:

[1] unable to earn enough through taxation, the state needs to borrow continuously to meet daily expenses – including its repayments on past borrowings.

[2] Better ratings (give commercial lenders more confidence and) make possible future borrowing on less painful terms.

[3] But ratings and investor confidence depend on Sri Lanka adhering to economic reforms drawn up the IMF to cut government spending and encourage private industry (for taxes), and thereby reduce government debt.

|

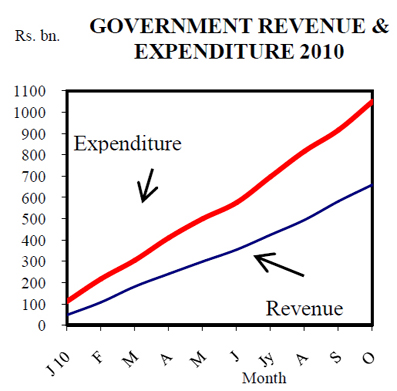

| Central Bank graph (31 Dec, 2010) |

See also this on how Sri Lanka's debt ratings compare.

Expectations

In October, the new debt ratings, and foreign investors willingness to buy government debt (i.e. lend it) of US$1bn were based on specific expectations:

[1] Sri Lanka would cut state expenditure (especially subsidies to Sinhala businesses and population) and its bloated state sector (currently employing 1.3 million people), including its massive military and its largely loss making state-run enterprises.

[2] Allow, and promote, the rapid generation of private industry, especially in the former warzones, enabling profits for both the economic progress of the collective population and taxes to pay for state expenses.

Firstly, the state is actively blocking development and economic revival in the war-torn Tamil areas (see these reports).

Secondly, despite its rhetoric, it is continuing with subsidies and other expenditures in support of the Sinhala population.

Despite pledges in the budget (see this also), President Mahinda Rajapaksa last week extended public sector salary increases, announced new subsidies for coconut farmers (despite the soaring prices for nuts) and raised the usage threshold for having to pay full rates for state-supplied electricity (more on this later).

'Mahinda Chintana'

Most state employees, coconut farmers and households with access to electricity are Sinhalese, with much of the Tamil areas barely out of a humanitarian crisis.

Amid the soaring cost of living, the new measures will no doubt boost the government’s popularity, particularly ahead of recently announced local government polls.

They are also in keeping with the economic logics of Sinhala-nationalist ideology, as set out in President Rajapaksa's manifesto, 'Mahinda Chintana'.

Although most Sri Lankan administrations have lived beyond their means (living on generous foreign aid), President Rajapakse’s regime pushed the policy of overspending to the limit.

Over the past five years the state has ramped up subsidies, buying back (nationalising) private companies such as Shell Gas and Sri Lankan Airlines, increasing public sector wages and, most importantly, massively expanding the military (which is ongoing, even though at the end of the war Sri Lanka’s army alone is more than twice as big as Britain’s).

The Rajapaksa government has also reversed some privatisations carred out by earlier administrations (See also the Sri Lankan Sunday Times' report on 'Re-nationalising').

Sovereign in debt

In June 2009, faced with having to default on its debt repayments and almost running out of money to pay for essential imports, such as oil and food, Sri Lanka was forced to turn to the IMF for a bailout loan.

In return for the IMF’s assistance, Sri Lanka reluctantly agreed to reign in its spending while increasing income through more regular and extensive taxation.

The IMF has repeated warned Sri Lanka about the rising cost of subsidies (See the abstract to this 2009 report, and this 2005 report) and urged it scale back its ‘recurrent spending’ on things such as salaries for public sector workers.

The IMF also identified loss-making publicly owned enterprises (see p4 here), such as the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB), as requiring urgent reform (including ultimate transfer to private ownership). The CEB supplies electricity at much lower than the cost of production, the difference being met from government funds.

At the same, the IMF wants the government to increase its tax revenue, including allowing and encouraging private businesses to flourish.

Words and deeds

The ‘investor friendly’ budget announced in November suggested the government would comply with these demands. Taxation was to be expanded, public sector pay increases held back, and from January electricity charges raised to a level closer to the cost of production so the government would no longer have to meet the difference.

Indeed, last month Barclays felt Sri Lanka's debt was better for investors than Vietnam's, precisely because of an anticpated reduced budget deficit and improved balance of payments next year.

However, within a month the government is retreating from these measures vindicating those, including the Wall Street Journal, who were sceptical of Sri Lanka’s budget promises (see also this).

If, then, else

Sri Lanka’s proclivity for overspending means that despite the IMF imposed austerity programme, total government debt increased by 10% in 2010 to US$41.2 billion, from US$ 37 billion at the end of in 2009.

The same month, the IMF noted that the trade deficit was widening, but accepted the government's promises, as did international ratings agencies,

When Standard and Poor’s raised Sri Lanka’s debt rating in October, it explicitly linked the move to the government meeting the IMF’s guidance, and warned the rating:

“could come under downward pressure in the event of substantial deviation from the IMF program, or if expectations on recovery in growth prospects and revenue improvements disappoint.”

However, both are almost certainly guaranteed this year: as ever, under Sri Lanka’s Sinhala-nationalist governing logic, as the S&P worried, "political expediency overrules fiscal-consolidation objectives."