The coronavirus pandemic has instilled a global sense of panic as the death toll continues to climb.

In the US 39,158 people have died from coronavirus whilst in Spain 20,639 people died and in Italy, 23,22, at the time of writing. Imperial College London has warned that if appropriate lockdown measures are not taken to curb the spread of the virus, millions could die.

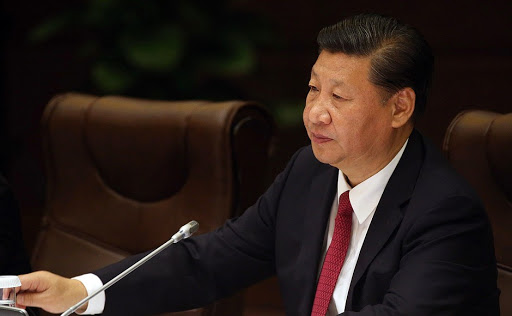

Political commentators have been quick to tout the success of China in dealing with the response and limiting the number of deaths, to 4,632 – despite the death toll from Wuhan being revised this week. According to Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, “China’s top-down approach seems to have done a pretty good job”. Praise for China’s rapid response however has given litany to a worrying apologia for authoritarian responses.

The gold standard?

In drawing comparisons to responses, China, Singapore and South Korea are often invoked as the gold standard. Whilst these comparisons are problematic, a common area of praise is in identifying potential carriers of the disease and acting early to isolate said individuals.

Technology has played a vital role in this process. The New York Times reports, that in hundreds of cities in China the government has mandated that citizens use a software on their phone which classifies them according a colour code - red, yellow, or green- indicating their contagion risk.

Similarly in Singapore, the Ministry of Health has utilised investigators to contact 6,000 people, often before they even knew that they may have the virus. Because of these efforts Singapore has currently been able to limit the number of deaths to 11.

Whilst this sounds like an ideal system to some, there is a darker side to this surveillance.

The Security State

When Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, a key policy focus for him was “internal security”. From when he took office to 2017, he increased spending on security in Xinjiang to nearly $8.4 billion, increasing the amount spent six-fold. This money was spent on surveillance, including cameras and facial recognition systems. China has complied a database of the city of Kashgar, with a population of 72,000, with a database of 68 billion records tracking peoples movements and activities.

The promise of security entices a worried public who in turn invite in further surveillance and militarisation. The constant presence of cameras on street corners, soldiers on patrol and drones whirling above, leaves you assured, or fearful, that someone is watching. Overtime they become the norm.

This surveillance has had dire consequences for the local population in Xinjiang. Over a million ethnic Uighurs and other Muslims have been detained in indoctrination camps. What little is known about these camps have come from government leaks but still the Chinese government continues to deny UN unfettered access to the region. China has defended its policies invoking the phrase “counter-terrorism”. Speaking on the matter, a spokesman for China’s foreign ministry, Mr. Geng Shuang, stated;

“It is precisely because of a series of preventive counterterrorism and de-extremism measures taken in a timely manner that Xinjiang […] has not had a violent terrorist incident for three years”.

This is sadly not simply an issue with China but speaks to the broader narrative of “internal security” with states around the world. In the US it was not only the unlawful surveillance of Muslim American’s after 9/11; it was the monitoring of Jewish Americans during the Red Scare; the internment of Japanese Americans during World War Two; and African Americans during the Civil Rights era. Today the UK’s PREVENT program, demands that those operating on the front-line of the public service and education monitor those they are supposed to help for signs of “radicalisation”. Far too often this has simply been an excuse to intimidate and monitor diaspora groups “such as Tamils, Kurds, Baluch and Palestinians”. The growing security state has been clamping down on perceived threats within its borders.

The Totality of the State

It is in this context that the COVID-19 emerged. And whilst it poses an existential threat to the public, in responding to the virus, states have pushed a securitised narrative. One which empowers the strong man; vilifies the foreigner; and delegitimises opposition. In the words of Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini;

"Everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state”.

This mantra is perhaps best illustrated in Sri Lanka.

Prior to the outbreak of the virus in March, Sri Lanka had recently elected the former Defence Secretary and Sinhala nationalist demagogue, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, as president. Rajapaksa’s record is marred in a series of human rights violations, but he rode a Sinhala nationalist platform that promised security from ‘foreign’ threats to electoral victory last year.

Rajapaksa’s election was in part driven by nativist fears over security following the Easter Sunday bombings in which over 250 civilians were killed, but also drew upon a deep history of racial hatred targeted towards Tamils and Muslims.

Sri Lanka’s response

Sri Lanka’s COVID response has placed the military at the forefront being led by accused war criminal, and head of the Sri Lankan Army, Lieutenant General Shavendra Silva. In a press statement Silva as he assumed the role, he told the public;

“To confide in members of the armed forces as guardians of the country.”

But as Tamil Guardian, editor-in-chief Thusiyan Nandakumar reminds us, this is the same military which has conducted mass atrocities against the Tamil population and has not seen any accountability for the abuses. In empowering the State, “Sri Lanka’s actions further cements a state-led narrative that normalises militarised methods for what should be civilian-led processes,” he wrote.

The state’s response reinforces and maps on to existing militarisation.

In early discussions of where to establish quarantine centres, Sri Lanka’s leprosy centre in Hendala, located in the South of Sri Lanka was proposed as an “ideal" location. This was quickly shot down with local protest from the largely Sinhala community and politicians. These centres were to be relocated to Batticaloa, in the east, home to Tamils and Muslims. Despite widespread protests from the native population there, the state did not flinch. According to a local epidemiology expert, this was a deliberate decision to “keep any outbreak far away from their [Sinhalese] areas”. Armed troops, dressed in full camouflage uniform, have been running these centres and also leading “disinfection” regimes across the island. A military accused of war crimes has been at the forefront.

Thus emerges a familiar narrative of Sri Lanka troops stationed at barracks on the peripheries, warding off foreign threats from the Sinhala citizenry. It is perhaps ironic that the threat comes as a virus, given racist narratives on the island that sees Tamils likened to demons and diseases. Similarly an early report on COVID exit strategies proposed racially profiling Muslims; identifying them as a key risk factor contracting the COVID-19 virus.

The coronavirus poses a challenge not simply to institutions or economies, but also to moral character and the politics that guides states across the globe. Will they fall back into familiar patterns? Trade autonomy for security; build barriers and walls; occupy and dominate, in service of a citizenry. Or do we move forwards? Will we reject the security mantra and demand transparency and accountability from governments? Will we have a human rights-based approach to dealing with this pandemic that protects civil liberties whilst safeguarding public health?

Just this week, Amnesty International in a video to Rajapaksa and other leaders around the world, warned that “leaders who threaten human rights are using a pandemic to expand and abuse their powers instead of focusing on helping doctors and nurses."

"To those leaders: we’re watching you,” it concluded.

As states continue to grapple with COVID-19, we must be vigilant and stand opposed to authoritarians.

.JPG)