(Photo provided by the World Bank)

The World Bank’s recent report on Sri Lanka highlights the devastating impact the coronavirus has had on the economy; with the country experiencing its worst growth rate on record, contracting 3.6 percent throughout 2020, with a massive 16.4 percent contraction in the second quarter alone. Economic recovery, the World Bank notes will be reliant upon foreign direct investment and normalising tourism.

Foreign Investment

Whilst the World Bank projects an optimistic growth of 3.4% in Sri Lanka; it follows the European Union’s announcement that it will review its GSP+ agreement in light of Sri Lanka’s decision to expand its draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA). In their statement, they further criticised the government’s imposition of import restrictions.

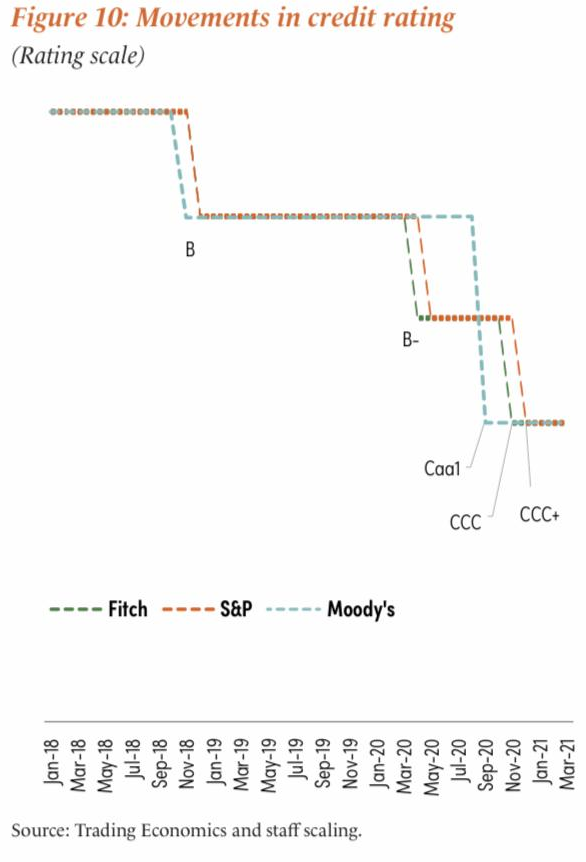

The World Bank further details Sri Lanka’s plummeting credit rating, across Fitch, S&P, and Moody, reaching a Caa1, CCC, and CC+ rating respectively in 2020. In September of 2020, Sri Lanka’s Finance Minister lashed out at Moody’s downgrade describing it as “reckless” and “unwarranted”.

The report notes that foreign direct investments have been “sluggish” with “financial inflows insufficient to meet external liabilities” and leading Sri Lanka’s reserves to reach an 11-year low in February 2021. In March the government was able to secure a currency swap worth US$ 1.5 billion with the People’s Bank of China however a shortage of foreign currency has led the exchange rate to depreciate by 6.5 per cent from January through March 17, 2021.

Trading relationship with India has been further hampered by the government’s unilateral withdrawal from the East Container Terminal agreement, worth an estimated $700-$800 million dollars.

Rohan Masakorala, maritime shipping expert and CEO of the Shippers’ Academy Colombo has sharply criticised the decision telling the Hindu, that it “gives potential investors here mixed signals, because the government’s position was volatile and not direction driven”. Industry experts have stressed the need to make the port an international hub as opposed to making it fully publicly owned noting that 81% of the total cargo arriving at the Colombo Port is transhipment cargo, while only 19% accounts for domestic cargo. The Hindu further notes that over 70% of the transhipment business is linked to the Indian market.

State-ownership and the militarised economy

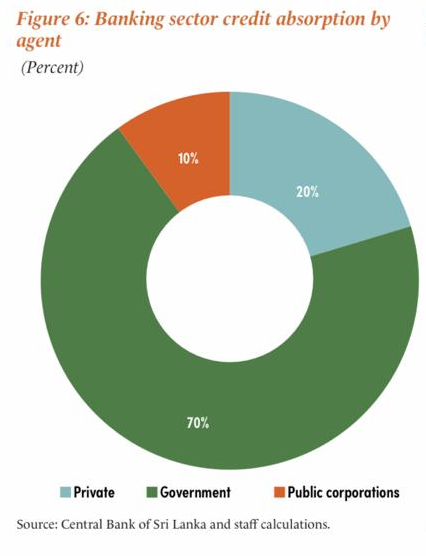

The World Bank’s report highlights the relative lack of bank lending to the private sector whereas “credit to the government and state-owned enterprises surged and accounted for 80 per cent of the total credit in 2020”.

This inequity has coupled with increasing militarisation of the economy which has persisted since the end of the armed conflict. Last month, the Oakland Institute reported that in Mullaitivu alone the military has “acquired more than 16,910 acres of public and private land”. The land occupied by the military has been used to promote tourism, as the armed forces continues to operate hotels and resorts, as well as to cultivate agriculture which is sold below-market rates, stifling livelihood opportunities for already impoverished Tamils in the North-East.

The Economist has highlighted this trend noting that generals are taking over civilian roles and are placed “in charge of customs, the port authority, development, agriculture and poverty eradication”. However, there is little reason to suspect that military men will “do a better job of running ports, reducing poverty or increasing crop yields”.

This is further worsened by the lack of accountability as, “the positions filled by officers have little civilian oversight”.

The poor bear the brunt

The economic downturn has been largely felt by the poorest in Sri Lanka who had the largest proportionate earnings shock while the smallest proportionate income losses were suffered by the richest. The latter tended to, the World Bank notes, “have formal, secure jobs and better access to digital technology that allows them to conduct wage work or business operations remotely”.

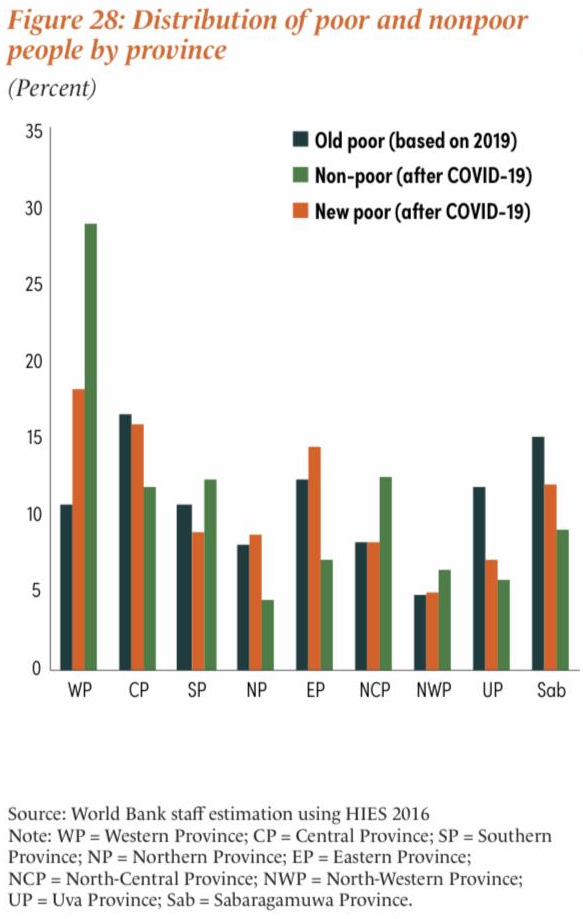

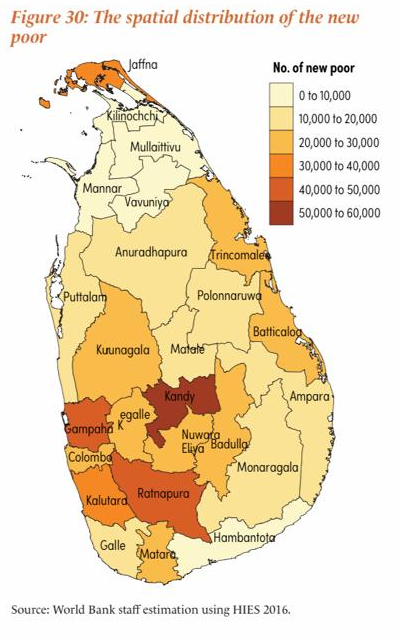

The $3.20 poverty rate is projected to have increased from 9.2 per cent in 2019 to 11.7 per cent in 2020 and the impact has varied across regions. Across the North-East the number brought into poverty outstrips those in poverty except for NCP where the levels are the same. In the Northern and Eastern provinces, the number of “non-poor” was fewer than those in poverty.

Photo of Council member and volunteer delivering aid - 25 March 2020

Whilst the World Bank has noted that the government has run welfare schemes to alleviate the impact of the pandemic however villages across the North-East have reportedly not received support, prompting the Tamil diaspora and local volunteers to help out instead. There were further reports of local volunteers being blocked from providing aid and even arrested.

An estimated 20,540 people across the North-East were further denied access to the government-run graduate scheme which aimed to provide employment for low-income families.

Military abuses

(Photo of Sri Lankan Garment Workers, Credit ILO Asia-Pacific)

Those in precarious employment in Sri Lanka were also reported to be subject to abuse. In 2020, textile workers in the Brandix garment factory suffered outbreaks of COVID pandemic with 1,036 employees and 361 of their close contacts have tested positive. In October, they filed a complaint to Sri Lanka’s Human Rights Commission which detailed “cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment” by Sri Lanka’s military which forced 98 factory workers, the majority women, into quarantine centres.

Read more here: Sri Lankan army denies abuse of factory workers and forced detention

Read the full World Bank report here