|

| Sri Lanka plans to become Asia’s hub port. Photo Sena Vidanagama/AFP/Getty Images |

The Co-Chairs’ statement of 21 November 2006 was an eyeopener for the Sri Lankan Tamil community.

The international community’s position, attacking the LTTE and defending the Sri Lankan state, was bluntly set out by US Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs ,Nicolas Burns, with representatives of the other Co-Chairs - EU, Japan and Norway - standing shoulder to shoulder with the US.

Inevitably, as has been noted by Indian analysts amongst others, the Co-Chairs' strong support for the Sri Lankan government has lead to desperation and total disillusionment with the international community amongst the Tamils.

But if the Tamils are bitter, it is about time.

Mr Burns was nothing if not forthright last week. And if they want to understand the international community’s perspective, the Tamils only need pay close attention to his words.

To begin with, for the international community, Sri Lanka is a unique collaborative project. Differences amongst international actors on other issues are set aside in pursuit of a common goal here.

Because that goal is one from which all international actors can benefit: to boost the global economy by turning Sri Lanka into a stable and secure commercial and economic hub.

Thus, from a geopolitical and geoeconomic perspective, the international community’s key objective in Sri Lanka is stability.

Mr Burns was explicit: “the Sri Lankan government has a right to protect the stability and security in the country.”

In short, Sri Lanka is an important site for the global economy. That doesn’t mean Sri Lanka’s own economy is important. Rather, it is what Sri Lanka can contribute to the global economy.

At a crucial location in the Indian Ocean (in the middle of important sea routes), Sri Lanka holds enormous promise for enhancing and enlarging commercial flows between Asia, the Middle East and the West.

If only it were stable.

Without guaranteed stability, Sri Lanka cannot benefit international trade in the long term (the point, again, is not whether Sri Lanka benefits from international trade, though that might be a bonus, expanding, as it does, the global market slightly).

In the short term, without stability and security the investment atmosphere in Sri Lanka cannot be conducive to the kinds of development needed to turn the island into a commercial hub for global trade.

Thus for the custodians of the global economy – US, EU and Japan, ensuring Sri Lanka’s stability is a pressing priority. The urgency is fuelled by accelerating global trade.

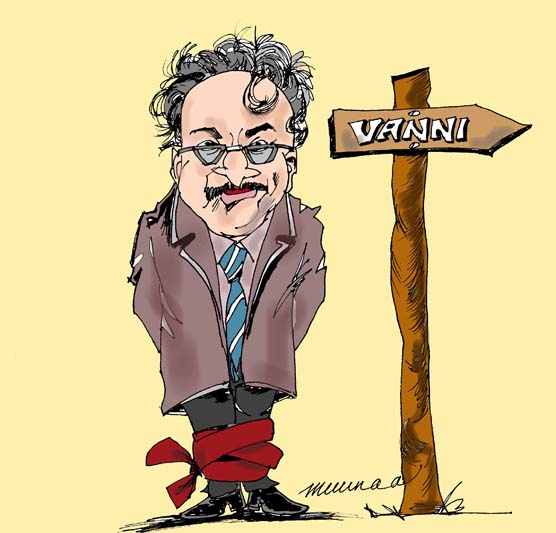

But the Tamil armed struggle violently disrupts this stability.

Indeed, the very existence of the LTTE, an armed non-state actor running a de-facto state in a large piece of the island and fielding a large naval force, is deeply antithetical to the international vision for Sri Lanka.

The resurgence this year of the simmering violence (mistakenly thought to have been banished by the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement), has also disrupted the international community’s hasty efforts also launched that year to resume Sri Lanka’s delayed transformation into a commercial hub.

This is no conspiracy theory. The international community has been always been clear that this is their goal (though of course it is the potential benefit to Sri Lanka that is pointed out, not that to the global economy or the national economies of the major powers).

The frustration for the Co-Chairs is that the Tamils seem oblivious to all this.

In fact, the ignorant Tamils are vociferously demanding things that are antithetical to this goal: asking for recognition of their right to self-determination, for independence, for acceptance of their violence and for the LTTE.

In reality, Tamil protests of oppression by Sinhala-dominated state are largely irrelevant to the international community’s calculations for Sri Lanka.

Asked about suggestions that some US officials sympathised with the Tamil demand for self-rule in their homeland, Mr. Burns replied: “we support the government. The government has a right to protect the [country’s] territorial integrity and sovereignty. [It] has a right to protect the stability and security in the country.”

Stability and security for Sri Lanka essentially means defeating and dismantling the LTTE. A political solution is a secondary issue.

This is also what stability and security mean for the international community: it is the LTTE’s armed struggle which is the prime impediment to Project Sri Lanka.

The oppressive policies of the Sri Lankan state may be distasteful to the international community, but are not necessarily a problem. These are not likely to disrupt the island’s investment atmosphere or disrupt Sri Lanka’s transformation.

When Mr. Burns says “we hold the Tamil Tigers responsible for much of what has gone wrong in the country,” he is thinking of Sri Lanka, the unrealised global commercial hub, not Sri Lanka, the Sinhala-chauvinist state.

In short, the two visions of Sri Lanka –the global trade hub and the Sinhala-Only land – are perfectly compatible.

This is why the Tamils have such a hard time getting their case heard. Indeed, the Tamils and their protests about discrimination are merely a nuisance to the international community.

Whilst we see the racial violence, the deaths of 90,000 civilians by state violence (including by blockade of food and medicine), and the systematic marginalisation of our people as central life-or-death issues, the international community sees these as unfortunate matters to be dealt with (non-violently) on the edges of the main business of facilitating global trade.

A quick overview of international engagement with Sri Lanka in the past three decades demonstrates the point.

In the late seventies it was clear that given its geographical location and strong, social indicators, that Sri Lanka had the potential to contribute to the global economy to an extent that Singapore has, possibly even more.

Sri Lanka’s staunchly pro-West first President, J. R. Jayawardene, visualised Sri Lanka as a free trade hub to rival Singapore. And that was long before China and India mushroomed as drivers of the global economy.

Jayawardene’s embrace of the IMF and World Bank drew in a flood of developmental funds that was proportionately greater than any other developing country, despite the mounting human rights violations, discrimination and repression

Even the state-sponsored anti-Tamil pogrom of 1983, a horrific catastrophe for the Tamils which caused international dismay, did not slow the inflow of foreign aid.

Since then, there has been consistent and ever-increasing support for the Sri Lankan military to wipe out the growing Tamil rebellion. This international support culminated in the endorsement of the ruthless ‘war for peace’ of the late nineties.

But the growth of the LTTE and its armed struggle has made Tamil outrage an unavoidable obstacle for the international community’s efforts.

It was only when Sri Lanka’s military failed to destroy the LTTE that the Norwegian-fronted international peace process was rolled out in 2000.

But even that initiative had containment and dismantling of the LTTE as its primary objective, not resolution of the conflict per se.

Tamil incredulity at international behaviour over the past four years stems from our confusion as to what the international community, led by the Co-Chairs, were focussed on.

Security for us meant protection from the Sinhala armed forces. Security for them meant no more LTTE attacks in the south.

Stability for us meant the return of normal life for our war-savaged community. Stability for them meant no return to violence by the LTTE.

Peace for us meant a lasting just solution. Peace for them meant the permanent disarming of the LTTE.

In short, it is Sri Lanka’s economic potential that matters most to them, not its domestic treatment of the Tamils.

Even despite its civil war Sri Lanka’s economy has expanded given its peerless position right in the middle of the expanding global trade flows.

In 2004, the Colombo port was the world’s fourteenth largest port by volume for transhipment. There’s also Galle and, of course, Trincomalee.

Last month Sri Lanka began expansion of a small airport in the south into a massive site capable of handling the world’s largest commercial jets.

The Malacca straits adjacent to Singapore are the shortest sea route for oil tankers travelling between the Middle East and Asian markets. This route allows shipment of nearly 80% of the oil to China, Japan, and South Korea.

Sri Lanka is halfway between the Middle Eastern oil producers of Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the Malacca straits.

Even in security terms, Sri Lanka provides an excellent staging post for US or European military powers interested in Asia or Australasia (in the late nineties, fifty British warplanes once transited through Katunayake airbase enroute to exercises in South East Asia).

The United States’ military has for several years been seeking bases across the world from which to project its awesome power, vital to protect global commercial lanes. Places like Sri Lanka are excellent sites.

But even without its potential as an ideal location for US/Western force projection abroad, a stable and secure Sri Lanka invaluable to the global economy and thus to its custodians.

Which explains the manifest lack of international interest in addressing the Sinhala-dominated nature of the Sri Lankan state. It explains the international eagerness to stabilise the state, irrespective of its acts against the Tamils.

In 1983, President Jayawardene infamously said before the July pogrom: “I am not worried about the opinion of the Tamil people. We cannot think of them. Not about their lives or of their opinion about us.”

In the rush to realise Sri Lanka’s commercial potential, this is also how the international community feels about the Tamils.

And it is the LTTE’s violence, not international goodwill, that, by holding up Project Sri Lanka, keeps the Tamil issue on the international agenda.