“I will make my people ungovernable!” Rajavarothiam Sampanthan exclaimed, banging on the table. He was at a private meeting with diplomats of a powerful Western state in 2016, his expression giving away his frustration over the failure of the ruling Sri Lankan government, then led by Maithripala Sirisena, to make progress on the Tamil national question. R Sampanthan was one of Sri Lanka’s longest-serving members of parliament and the leader of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), the main political coalition representing the Tamils of the country’s North and East. He had promised Tamils ahead of the 2015 election that there would be a political settlement to meet their long-standing demands for autonomy by 2016 – and when that did not materialise in time he promised it by 2017. A few months prior to the meeting with the diplomats, Mavai Senathirajah, the leader of the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi – Sampanthan’s political home, also known as the Federal Party – had told Eelam Tamil activists and politicians from across the world gathered in the United States that the TNA would embark on a campaign of civil disobedience if the Sirisena-led government failed to come to an agreement with Tamil nationalist representatives in parliament. He was evoking the Federal Party’s legendary 1961 satyagraha against the implementation of the Sinhala Only Act, a landmark in the disenfranchisement of Sri Lanka’s Tamils as it prescribed Sinhala as the country’s only official language. On that occasion, a campaign of civil disobedience had managed to bring the civil administration of the North and East to a standstill.

Spoiler alert: Sirisena did not make progress on the Tamil issue. Sampanthan did not make his people ungovernable. And the TNA did not embark on a civil disobedience campaign.

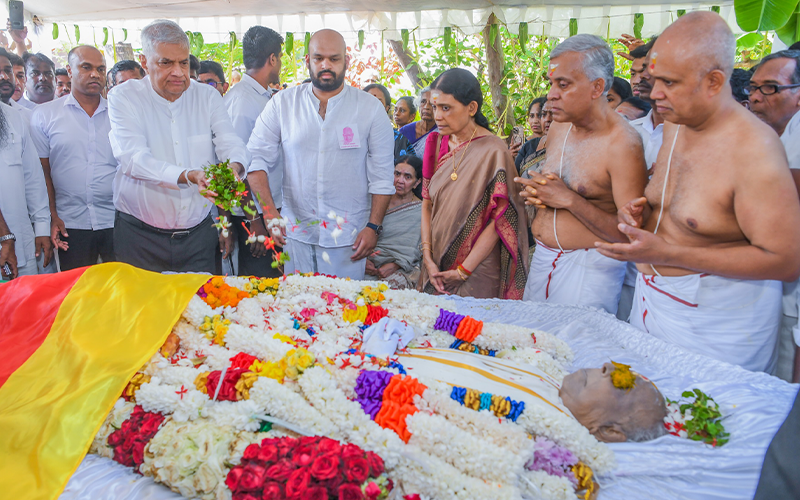

Since his death in June, glowing tributes for Sampanthan have poured in from politicians and diplomats in Colombo, highlighting his pragmatism and his undeniable service. India’s prime minister and foreign minister praised his advocacy in pursuit of justice and dignity for Tamils. Some, including senior TNA figures such as M A Sumanthiran, pointed out his commitment to a “united, undivided, indivisible” Sri Lanka, pre-empting any questioning of his past affiliation with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

Seeing the volume and tone of such condolence messages, particularly from non-Tamils, one could reasonably expect a similar, if not more emotional, response to his death from Tamils themselves. After all, if Sampanthan was the leader the Tamil people needed – as he clearly was in the eyes of the country’s Sinhala-dominated South and much of the diplomatic community – wouldn’t his death warrant an outpouring of grief among his people?

Yet there has been none. The “pragmatism” that the Sri Lankan state and foreign diplomats so adored served to strip Sampanthan of the standing he had had in the Tamil community before the end of Sri Lanka’s 26-year war in May 2009. The responses to his death from within the Tamil nationalist polity, of which he claimed leadership, have been rather muted, with only some perfunctory condolences, RIPs and Om Shanthis. Tamil WhatsApp groups usually abuzz with emotional commentary have stayed largely silent beyond sharing the bare news of his death. Only a handful of public commemoration events have been held in the days since his passing, virtually all of them organised by his party or those close to it.

Those from the North and East who commemorated him did, however, highlight his past links to the LTTE. The TNA leader Shritharan Sivagnanam, for example, said Sampanthan was a leader endorsed by Velupillai Prabhakaran, the leader of the LTTE, and that the struggle for the Tamil nation will continue in his absence. Shritharan’s statement gave some indication of why Sampanthan and his party continued to gather votes and appeared to be well supported by the Tamil community – a reason that his supporters in the South often ignore. His history with the LTTE – he endorsed the organisation as the sole representative of the Tamil people and led a union of Tamil parties supporting the LTTE’s efforts – meant there was a significant section of the Tamil population that felt not voting for the TNA after 2009 would be a betrayal of the Tamil struggle. The TNA, including Sampanthan, knew this and leant into pro-LTTE and pro-nationalist rhetoric through its local cadres. In effect, Sampanthan and Sumanthiran portrayed a “moderate” face in the South and to the international community even as the bulk of the TNA’s leaders and foot soldiers continue to follow a more radical Tamil nationalist ideology in line with the history of the Federal Party and the LTTE.

Sampanthan failed the Tamil nation at the moments it needed a courageous, elder statesman-like figure the most. During the ceasefire in the war from 2002 to 2008, at the height of the LTTE’s power, he was happy to benefit from proximity to the LTTE – but he distanced himself from the organisation as soon as it became clear that the war would be lost. During the final phase of the war, he was literally absent, ensconced at his other home in India, ignoring phone calls from fellow parliamentarians such as Gajendrakumar Ponnambalam. Much of the frantic negotiation with the Sri Lankan government in the last days of the fighting – including for the surrender of senior LTTE members, which ended in their extrajudicial killings – was left to other TNA leaders such as Ponnambalam and Ariyanayagam Chandranehru.

One would have expected Sampanthan, as the only significant Tamil leader left after May 2009 and the end of the LTTE, to have grasped the moment with both hands. After the bloodbath that ended the war, there was widespread international support for Tamil demands for justice and accountability, and the TNA could have played a leading role in advancing the Tamil struggle. More importantly, a battered Tamil nation had just emerged from its biggest calamity, and its people were looking for a leadership that would help them process the genocidal brutality they had endured at the hands of the Sri Lankan state.

Instead, Sampanthan chose the more comfortable, but ultimately fruitless, task of meekly seeking concessions from the same Sinhala political elite that was responsible for the violence. Perhaps the high point of this Colombo-centred strategy was the TNA’s decision to unequivocally support the Sirisena-led “unity government” of 2015 – a coalition that included numerous minority-led parties and notably excluded the Rajapaksas, who bore ultimate responsibility for the worst of the war-time abuses. That year, in a fit of enthusiasm for the newly formed government, Sampanthan became the first Tamil leader since the introduction of the 1972 republican constitution to attend celebrations for Sri Lanka’s Independence Day, still considered a black day by the Tamil people. Sampanthan defended his attendance at the event and his acceptance of the “lion flag” – the national flag of Sri Lanka, rejected by many Tamils as a symbol of Sinhala supremacism – as “palaiya kathai”, an old and resolved matter. The TNA even dithered on the question of federalism, a key part of Tamil demands for autonomy in the North and East, with Sumanthiran saying in 2018, “I won’t say it is needed, we can expand the existing provincial council system, our people are ready to accept that as a solution.”

The TNA’s symbolic capitulations in this period were both remarkable and predictably futile. Anyone possessing even a glancing familiarity with Sri Lanka’s political history would have been able to predict what happened next. In 2015, Sirisena appointed the current president, Ranil Wickremesinghe, as his prime minister. The fragile Sirisena-Wickremesinghe alliance made no meaningful progress on resolving, let alone addressing, Tamil demands. Three years later, it became apparent that the TNA’s support for Wickremesinghe’s United National Party, which held the majority of ministerial posts in the “unity government”, merely delayed the inevitable. In October that year, Sirisena sacked Wickremesinghe as prime minister and appointed Mahinda Rajapaksa in his place, leading to a constitutional crisis. In 2019, Mahinda’s brother Gotabaya, who headed the armed forces during the war, came to power as president, and continued the Rajapaksas’ brand of unvarnished Sinhalese-Buddhist chauvinism. The TNA’s strategy lay in tatters and its reputation was considerably weakened.

Sampanthan’s eagerness to capitulate in the vain hope of concessions from Sinhala political leaders cannot be put down to just naivete or optimism; he had been in Sri Lankan politics for too long to be that simple. Instead, we are left to evaluate his politics in light of its primary consequence: maintaining a position of relevance for himself and his fellow travellers in the political circles of Colombo. It is no surprise that the most gushing tributes for Sampanthan have come from the capital; this was, after all, his political home, and he was an insider there.

He maintained this insider position through most of his career, and this meant that he shunned the active agents of Tamil nationalist politics, with only a brief exception during the Norwegian-led peace process when he led the coalition supportive of the LTTE. In the post-2009 era, the central and most effective actor in Tamil politics has been a transnational network of civil-society organisations and social movements spread across the Tamil homeland and the diaspora, advocating for such things as accountability for war-time crimes, genocide recognition, justice and demilitarisation. Sampanthan studiously avoided engagement on these fronts and with these forces.

The upshot of this was that TNA was left to play catch-up as the agendas of accountability and genocide recognition advanced. Left outside the main theatres of political action and struggle, the TNA and Sampanthan clung on to Colombo and in this way became less and less relevant. The TNA today has dwindling capacity to shape, let alone lead, the networked politics of the Tamil cause. This also means, paradoxically, that it is of less relevance to Sinhala political elites. It has no real capacity to bargain as it has nothing to bargain with; it cannot command the broader Tamil movement to call off protests, to drop demands for accountability or even to come up with a unified position on federalism, because the TNA simply has no purchase over it. The only thing it can really deliver is votes, and even that less reliably than before. The TNA does, however, have one function left in Colombo; it allows Sinhala politicians the pleasing illusion of engaging with Tamil demands via engagement with the TNA, without any of the discomfort of actual reform and hard bargaining.

Sampanthan is often compared to S J V Chelvanayakam, a prominent leader of the Eelam Tamils before and after the end of colonial rule and the widely revered founder of the Federal Party. Chelvanayakam famously, and unsuccessfully, negotiated on two occasions with Sri Lankan prime ministers, but the comparison between him and Sampanthan is superficial. Chelvanayakam transformed Tamil politics in Sri Lanka. He built a popular base for the Federal Party and, through that, an ideological foundation for Tamil nationalism. He consolidated a territorial identity through mass protests and electioneering and reached out to the international community as well as the then-fledgling Eelam Tamil diaspora to advance Tamil demands. In contrast, Sampanthan’s main achievement was to maintain his position in the court politics of Colombo amid the epochal defeats and advances of Tamil nationalist politics over the past decade and a half.

Under Sampanthan’s leadership, the TNA largely spent the capital and momentum it secured during the peace process, with no tangible benefit for the Tamil people in return. Any remaining electoral support it has is an effect of legacy and the mundane workings of patronage politics, which sits alongside, but does not displace, Tamil nationalist ambitions. Perhaps Sampanthan’s most telling legacy is that the question of his successor rouses little interest or animation among the Tamil polity. Beyond the cramped political horizons of the TNA, Tamil nationalist politics is focussed elsewhere, in sites of struggle both local and international.

This piece was originally published on Himal magazine

%20new%202.jpg)

%20new%203.jpg)

%20new%204.jpg)

%20new%205.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG) A memorial was held to honour the memory of the more than 140 Tamils who were killed in the Navaly Church Massacre on July 9, 1995, at St Peter’s Church in Navaly.

A memorial was held to honour the memory of the more than 140 Tamils who were killed in the Navaly Church Massacre on July 9, 1995, at St Peter’s Church in Navaly..JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)